Research findings from Mozambique and Bangladesh

Climate change is now affecting every country on every continent, disrupting national economies and individual lives.

Women and girls disproportionately bear the brunt of climate-related events and environmental stress. Women comprise 20 million of the 26 million people estimated to have been displaced already by climate change. And they are more vulnerable to the impact of climate change because they lack power. Ultimately, climate crises deny women the ability to control their own fertility and hence their own lives.

Learn why we need women-led climate justice through real women’s stories

Visit IpasClimateJustice.org

Between 2020-2021, Ipas conducted qualitative research in Zambezia, Mozambique and Khulna, Bangladesh. We wanted to understand how women’s experiences with climate change impact their sexual and reproductive health decisionmaking, behavior, and outcomes in cyclone-prone communities. Mozambique and Bangladesh are both highly vulnerable to cyclones and flooding, making them among the countries most severely impacted by climate change—which in turn exacerbates poverty and poor health outcomes for rural and coastal populations.

Overview of findings

- Climate change disproportionately impacts women and girls by exacerbating existing gender inequalities, disrupting access to sexual and reproductive health care, and reducing their already limited economic opportunities.

- Climate change directly and indirectly affects women’s contraceptive use, fertility intentions, pregnancy outcomes, vulnerability to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), economic roles, and sexual health.

- The time immediately before, during, and after extreme weather events, such as cyclones, is when access to care for contraception, pregnancy and abortion is most compromised.

- Pregnant women are particularly at risk due to climate change, facing increased risk of miscarriage, early labor, and pregnancy complications that could lead to illness, injury or death. Adolescent girls experience increased risk of SGBV, child marriage, early sexual debut and pregnancy.

Key finding: Women have solutions

That’s why we need women-led climate justiceBefore Cyclone Idai hit the port city of Beira, Mozambique, Fátima João had a house to live in with her husband and four children. She had just bought the children notebooks, backpacks, and pencils for school. But the storm destroyed everything. Photo by Amilton Neves for Ipas

Women play a leading role in helping their families and communities survive extreme weather events and adapt to climate change, but opportunities for women’s participation in climate action decisionmaking bodies is insufficient—especially at the leadership level. Climate action that is not gender inclusive risks making existing problems even worse. We need to listen to women and girls.

Our study participants brainstormed ways to lessen the impact of climate change on women and girls, focusing in on these five recommendations:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Involve people most affected by climate change—including women and youth—to develop and lead climate action efforts that include reproductive health.

"We can all sit together and discuss what is best to do. If everyone works together, then it will be possible to deal with the situation."

In-depth interview participant, age 19, Bangladesh

Our method

Bangladesh: We conducted our study in Chalna Bazar, Bajuya, Lawdube, and Tildanga in Dacope upazila of Khulna division due to these communities’ experience with Cyclone Bulbul in November 2019.

Mozambique: We selected communities in Mocubela, Maganja da costa, and Derre districts due to their experience with Cyclone Idai in March 2019. For this study we collaborated with the Provincial Health Directorate and Provincial Health Services of Zambezia as well as the National Institute for the Management and Reduction of Risk of Disasters.

Research was conducted between 2019-2021 with ethical approval from the Bangladesh Medical Research Council and the Committee for Bioethics in Health of Mozambique.

We interviewed 19 key informants with expertise in the sexual and reproductive health of their communities or in climate change resilience and adaptation. This included representatives from disaster risk management committees, community leaders, community health workers, local government representatives, community-based organizations and women’s groups.

We held 14 small community dialogue meetings with women ages 15-49. Participatory activities at these meetings included free listing and ranking, reproductive health lifelines adapted to include climatic events, and community action planning.

We also conducted in-depth interviews with 29 women about their personal experiences with climate change and its impact on their sexual and reproductive health and rights. Some women participated in both a community dialogue meeting and an in-depth interview.

Age: About half (48%) of participating women were 15-24 years old, while the other half were ages 25-49.

Marital status: In Bangladesh, all women were married, widowed, or separated, while in Mozambique, half of women were married and half unmarried.

Our findings in detail

1.

Climate change directly impacts sexual and reproductive health

2.

3.

4.

Gender norms and inequality magnify the impact of climate change by denying women power to make critical decisions

5.

1. Climate change directly impacts sexual and reproductive health

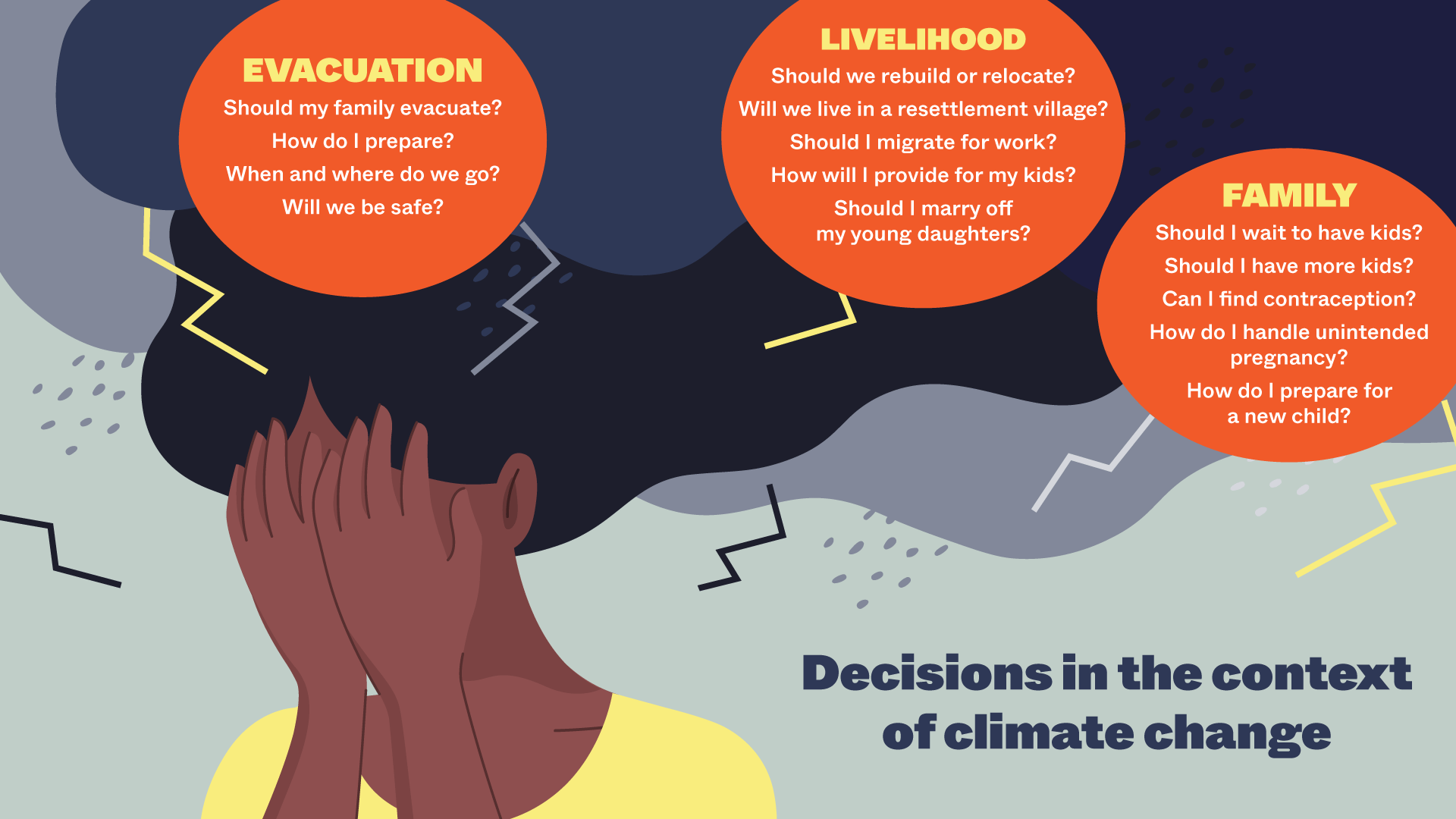

Our interviews and meetings with women and girls clearly showed that the conditions caused by climate change directly impact sexual and reproductive health outcomes. Climate change limits and interrupts access to contraception—particularly during and right after extreme weather events like cyclones. During a weather event, women may forget to pack their birth control for evacuation because their primary focus is survival. For others, their medicines are destroyed by the storm or washed away in flooding. Women and girls told us it’s usually impossible to access health centers or pharmacies for weeks after cyclones due to the flooding and devastation to the built environment. In turn, women face unintended pregnancies and must make difficult decisions—or even worse, have little control to make their own decisions due to cultural norms that deny women power.

Illustration by Marcita

How climate change contributes to unintended pregnancy and the need for abortion

Increased risk of SGBV*

Risk of SGBV while collecting relief and at cyclone shelters

- Economic crisis increases intimate partner violence

*Sexual and gender-based violence

Economic insecurity and crisis

Food insecurity

- Need to engage in risky work

- Fewer paid work opportunities

- Destruction of property

- Temporary or seasonal migration

Interrupted contraceptive use

Damage to health and transportation infrastructure

- Forgetting to pack birth control

- Being under-prepared for extreme weather events

- Birth control destroyed by storms

- Trapped in place for weeks due to flooding and destruction

Impact on children

More vulnerable to injury, drowning, starvation and malnutrition

- Fear of losing children or being unable to protect them

- Children’s education interrupted

Changing fertility intentions

Fear of being unable to protect, educate, and feed children

- Desire for more children (usually sons) to protect against future economic insecurity

- Desire to not have children or delay until feeling prepared

Impact on pregnant women

Increased miscarriage and premature labor

- Unattended births in cyclone centers, boats, on the road and at home

- Increased birth complications and maternal and newborn deaths

- Fear of pregnancy during a future climate disaster

How women describe the impact of climate change on their reproductive health

Irregular and difficult menstrual cycles

- Extreme period pain

- Poor menstrual hygiene

Unintended pregnancy

- Early and teen pregnancy

- Forgotten, missed, and destroyed birth control pills

-

Pregnancy complications

- Miscarriage

- Childbirth in cyclone centers and boats, on the roads and under trees

- Unassisted labor and labor with an untrained assistant

- Early labor and premature birth

-

Need for abortion

-

Difficult to access health facility-based abortion care

-

Self-managed abortion using unsafe methods

-

Postabortion complications

Infections, disease, and injury to reproductive organs

- Urinary tract infections

- Vaginal sores

- Vaginal itching, irritation and discharge

- Wounds in uterus

- Tumors in uterus and uterine cancer (this may include cervical cancers based on descriptions provided)

2. Climate change intensifies economic crisis and family instability

In Mozambique, interview participants explained that women tend to be the ones primarily responsible for farming and food production. As a result, they are disproportionately impacted by devastation to the agricultural sector. The most fertile farmland also tends to be in the highest-risk areas for extreme weather, called “risk zones.” Resettlement neighborhoods set up by the government are in “safe zones” not ideal for farming, with few alternative economic opportunities nearby. Resettlement neighborhoods are primarily inhabited by women and children, while men commonly migrate to cities or neighboring countries in search of work.

As a result, many women and their children in the communities we studied in Mozambique lead an unstable, semi-nomadic lifestyle, frequently migrating between their farmland and resettlement neighborhoods. Mothers either bring their children with them, which interrupts their education, or else leave them behind at the resettlement centers for extended periods of time. Some women have decided to remain permanently on their farms in risk zones to avoid constant migration.

In Bangladesh, a central theme interview participants identified was that women lack opportunities for paid work outside of the home due to cultural norms around their role as caregivers and household workers. Climate-induced migration leaves many women to care for their families alone. Women who become heads of household in this way—in addition to unmarried, widowed, or divorced women—are particularly vulnerable to violence and poverty. They described resorting to jobs that put their reproductive health at risk—such as fishing waist-deep in polluted waters and transactional sex—to feed their children and save money for future disasters.

3. Climate change makes women more vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence

In both Mozambique and Bangladesh, we found that the climate crisis intensifies sexual and gender-based violence. Destruction to housing, food sources and jobs can force women and girls to shelter in unsafe locations, travel long and unsafe routes for food and water, and resort to work that puts them at higher risk for violence. Exploitation and transactional sex are a particular threat to young girls experiencing economic crisis.

In Bangladesh, cyclone centers built to provide refuge during extreme weather events unintentionally put women and girls at risk for sexual harassment and rape due to crowded conditions, poor security, electricity outages, and lack of separate spaces and toilets for men and women. Women in both countries reported experiencing sexual harassment and abuse while collecting disaster relief after cyclones. And interview participants directly linked economic instability and stress in the aftermath of extreme weather events to increases in intimate partner violence, dowry and in-law abuse, transactional sex, sexual harassment, and early or child marriage.

Illustration by Marcita

4. Gender norms and inequality magnify the impact of climate change by denying women power to make critical decisions

Women’s traditional role as caregivers means they play a lead role in preparing their families for evacuation before a storm and the many decisions that go into that preparation. Yet, at the same time, they often lack the power to decide if and when to evacuate.

In Mozambique, one woman explained that she could not seek emergency health care during a cyclone because her husband was not around to grant her permission. In Bangladesh, the practice of purdah—which includes full-body clothing coverage to avoid being seen by men—means that some women are not allowed to go to cyclone centers, where men and women mix in crowded conditions. Traditional clothing also restricts their movement, hindering their ability to swim and run and increasing the risk of drowning and injury during a storm.

5. Climate change is shifting women’s fertility intentions

Study participants in both Mozambique and Bangladesh had differing opinions about the impact of climate change on their fertility intentions. Due to the increased vulnerability of pregnant women and children to climate change, women fear being pregnant and losing children during climate disasters. Many participants described not wanting to have more children in the wake of disasters, as they find it difficult to protect, feed and care for the children they already have.

Others felt the opposite, intentionally bearing more children to protect against becoming childless during a climate disaster. A key informant in Bangladesh explained that having at least one son is important for ensuring parents’ future financial security. In both countries, some participants also reported no impact on their reproductive decisionmaking. Regardless of their opinion on the role of climate change, most women described the need to prepare for children with similar factors—such as having an education, a home and enough money—which can be directly impacted by climate change.

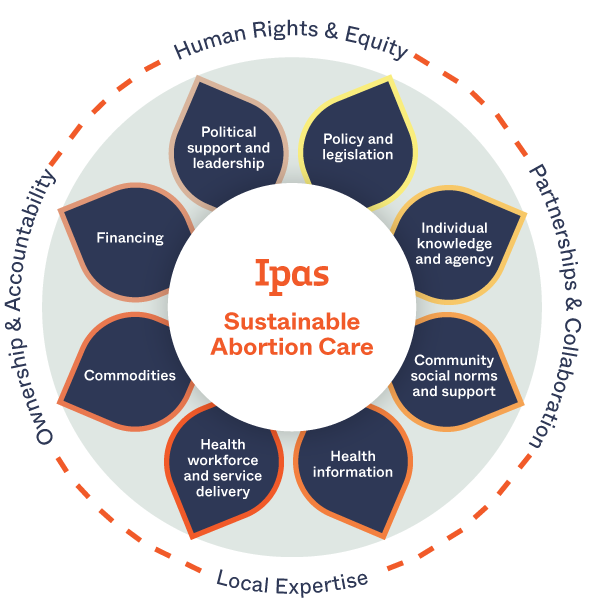

What Ipas is doing

Ipas is working to advance women-led climate justice as a technical leader, skilled convener, local partner, and advocate committed to climate, gender and reproductive justice. We use a comprehensive, intersectional approach that works across communities, sectors and institutions to build sustainable abortion ecosystems.

Our goal is to integrate abortion access and sexual and reproductive health and rights into climate justice efforts at the local, regional and global levels. We aim to leverage our expertise and relationships with ministries of health, local partners, and communities to advance climate-resilient health systems and pathways to care. Through our intersectional partnerships, solutions-oriented research, and locally rooted programs, we’re working for a world in which women and girls have bodily autonomy, are resilient in the face of climate change, and have the power to determine their own futures.

We invite you to continue engaging with us:

- Join the SRHR and Climate Justice Coalition

- Connect with Ipas to learn more about this work and explore ways to collaborate

Full results and peer-reviewed publications from this research coming soon. Suggested citation for this webpage:

Ipas. (2022). New research is in: Climate change impacts women’s sexual and reproductive health. Ipas.org. www.ipas.org/our-work/climate-justice/climate-change-impacts-womens-sexual-and-reproductive-health

* More research is needed on the linkages between climate change and sexual and reproductive health and rights. Ipas will be pursuing further research opportunities, alongside partners, and we welcome interested organizations and funders to contact us for possible collaboration.

Ipas gratefully acknowledges Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development for funding a portion of this research.

Learn why we need women-led climate justice

Our visual storytelling collection highlights the connections between reproductive justice and climate justice through real women’s stories.