With unsafe abortion remaining a leading cause of maternal death in Nigeria, it is critical that women with disabilities have access to comprehensive reproductive health services—including contraception and safe abortion—free from fear, stigma, and shame, and with the dignity every person deserves.

In Gombe State, Ipas Nigeria works with Ipas Collaborative Fund grantees SAIF Advocacy Foundation to advance a disability-inclusive initiative expanding sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) for women with disabilities. The project targets systemic change from healthcare provider attitudes to physical infrastructure, while ensuring women receive accurate SRHR information. By also helping civil society organizations become better equipped to design inclusive programs, and communities better mobilized to support access to contraception and safe abortion services, this initiative is achieving sustainable results in Gombe state and beyond.

When women with disabilities receive compassionate care from providers who understand their unique needs, they experience fewer barriers to safe abortion and contraception, leading to healthier, more autonomous lives.

Inclusive solutions center lived experience

The cost of being ignored

Hannatu Tila takes time to understand Munira’s disability and how it affects her health concerns.

A growing movement for dignity and change

“We’ve really had a lot of changes. And those barriers and gaps have reduced drastically,” shares Munira. “For instance, now if I should visit the hospital, and I’m about to lose my balance, people would stand up and catch me but, in the past, they’d let you fall… Nurses have been trained. One nurse received a query letter for mistreating me.”

Infrastructure improvements have made facilities more accessible, and people with disabilities are getting the specialized care they need.

“Regarding the issue of ramps… we can [now] access various parts of the hospital without any disruptions. In the past, if I wanted to visit, my mind was never at rest—I kept thinking I might not be able to get through. But now they’ve repaired the place; even someone in a wheelchair can pass without difficulty.

“We don’t follow queues anymore,” she adds. “As soon as we arrive, they explain to the crowd that we have to be prioritized.”

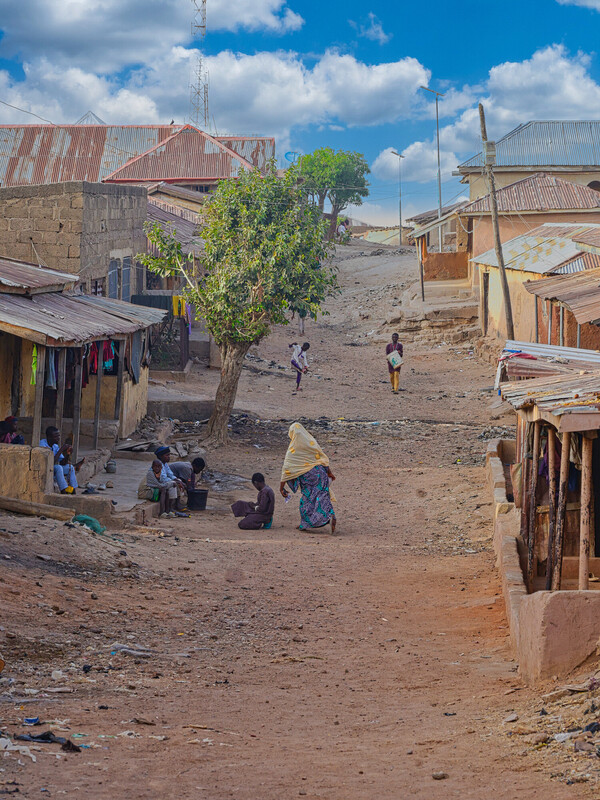

Back home, Munira feeds her family’s goats. With inclusive and accessible care, Munira’s medical appointments are just another part of her day.