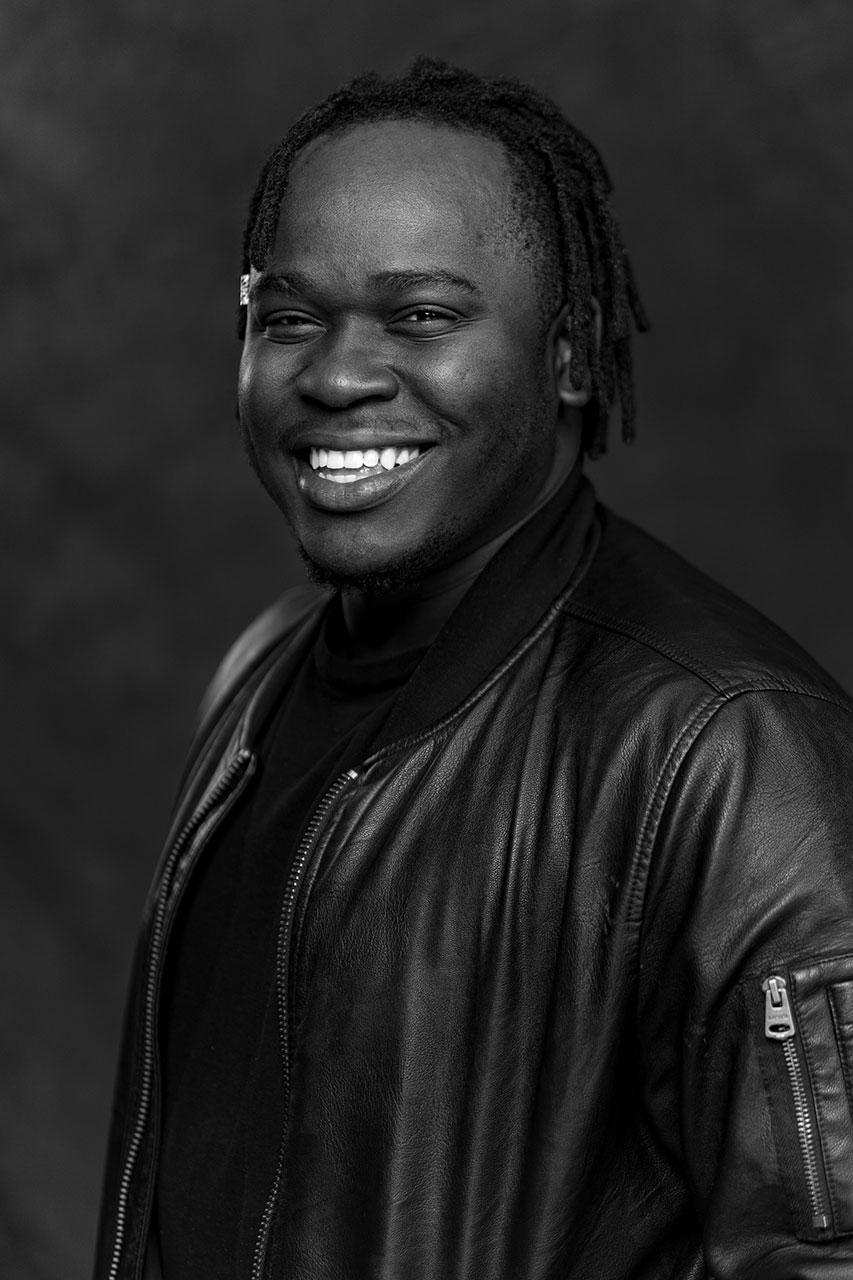

For too long, stories from Africa have been told from the outside looking in. Photographer and storyteller Kondwani Jere is shifting that lens, bringing deep listening and a learner’s mindset to every story he helps carry into the world.

Based in Malawi, Kondwani’s work explores identity, health, gender, and social justice. He approaches visual storytelling not as extraction but as invitation rooted in trust, consent, and a deep respect for those he photographs. In this conversation, he shares how visual storytelling became his way to witness with care, why Ipas’s approach stood out, and how a girl named Chinsinsi changed how he sees resilience.

Why did you choose a career in visual communication?

It wasn’t a straight path. I didn’t grow up with a camera in hand or dream of galleries. But I’ve always been drawn to people and their stories, especially the kinds of stories that don’t usually get told with care.

Visual storytelling became my way to witness people fully. To slow down and say, “I see you, and you matter.” I chose this work because it lets me hold both truth and beauty at the same time. A photograph or a film can carry a story across oceans. It can shift how someone is seen and sometimes, even how they see themselves.

That still moves me.

But over time, I’ve also come to see this work as a kind of responsibility. Photography and film give me what I call “the privilege of access”: an unfiltered doorway into people’s lives. That kind of access is never owed. It’s offered. And it comes with trust. For me, that trust is sacred.

I believe visual storytelling holds real power. And with power comes the duty to handle it with care, not just in how I document people, but in how I carry their stories forward. That’s the burden and the blessing of the work. And it’s why I keep doing it.

What does ethical storytelling mean to you?

This one is close to my heart hey and drives much of my practice and approach.

For me, ethical storytelling starts long before the shutter clicks. It begins with presence. With listening. With asking, not assuming. It’s about recognizing that when someone lets me into their life, they’re offering something real and fragile. That kind of trust carries weight.

Over time, I’ve learned to ask difficult but necessary questions: Who is this for? Who gets to speak? What might be misunderstood if I don’t listen well enough? What’s my place in this story, and what’s not mine to tell?

Ethical storytelling, especially as an African practitioner, carries another layer. For too long, stories from our continent have been framed through the lens of power, often not our own. Narratives have been extracted, dramatized, and flattened to fit a distant audience’s expectations.

So I hold a deep responsibility not just as a storyteller, but as a custodian of voice, memory, and meaning. My role isn’t to simplify or dramatize someone’s experience. It’s to hold space. To honor complexity. To reflect people as they are— not as symbols, not as victims, but as full human beings with agency, dignity, and pride.

I find that then that’s where the real work is. That’s the burden and the privilege of doing this well.

Why were you interested in Ipas’s proposal to document the interrelated issues of child marriage, teen pregnancy, and school dropout in Malawi?

Because these aren’t abstract “development issues” to me. They’re lived realities that are close, familiar, and personal. I’ve grown up surrounded by them. Friends, classmates, neighbors—girls whose paths were shaped or sometimes cut short by forces far beyond their control.

And yet, even with that proximity, working in Nkhotakota opened up a different layer of understanding for me. I saw just how heavy the odds can be in certain environments: the burden of silence, the weight of expectation, and the quiet compromises girls are forced to make just to survive let alone dream.

What drew me to Ipas’s proposal was that it didn’t flatten these experiences into statistics. It made space for nuance. For complexity. For emotion. It invited the girls to speak for themselves, in their own words and presence. That matters.

It also wasn’t a fly-in, fly-out assignment. The approach was grounded, rooted in place and in people. It gave room for listening, not just documenting. That gave the work integrity. It allowed me to not only contribute as a storyteller, but to show up as a learner. And I carry what I learned with me.

This was a story I wanted to help tell not because it was easy or dramatic, but because it was real. Because it deserved care.

Is there a person from this project that stands out to you? Why?

From the moment we met, she lit up the room. She was bold, expressive, and full of life. You could tell she had dreams, questions, plans and she wasn’t afraid to speak them.

Photographing her didn’t feel like “taking a picture.” It felt like being invited into her world for a moment. A world where, despite everything she’d been through, she still stood tall and chose to be seen.

When I look at her photo now, I see a girl holding two things at once: a deep knowing and a youthful hope. Her face carried the weight many girls are forced to bear far too early, but also the refusal to be defined by it.

She reminded me that strength doesn’t always come wrapped in silence or stillness. Sometimes, it’s loud. It’s present. It’s full of fight.

And she helped me understand the true heart of this story.

What’s something you’d tell your younger self, as you worked to carve a career for yourself?

I’d say, you don’t need to rush to be understood. Do the work that feels true, even if people don’t get it at first.

You’re not here to compete. You’re here to create.

Trust your rhythm. Stay grounded. And let your work be in conversation with the world, not in conflict with it.

And maybe most importantly: You don’t have to carry everything alone. Let people in. Let them see you, too.

Ensuring girls’ futures

A holistic approach to tackling child marriage, teenage pregnancy and school dropout